Where are venture-size returns in Africa?

Fintech, Commerce and the future of the VC model in the continent

Venture Capital in Africa is on a long-term growth trajectory.

Sure there was a significant drop (-21%) in funding after the 2021-2022 gilded era of African tech - when capital was cheap & money from abroad made up more than 75% of the total investments.

But we are still just at the beginning, and a few graphs can show us why.

In 10 years, dollars invested in tech startups grew from 400M in 2014 to 4.5B in 2023.

That’s a 25% CAGR and there’s plenty of room for growth. Why?

The “tailwinds” driving its growth: smartphone access, internet penetration, digital literacy, and financial inclusion.

Also, the post-2022 funding winter is mainly driven by a drop in growth stage rounds. It is bad as more companies die / will die as they fail to secure follow-on funds.

But early-stage activities keep growing, meaning new models will be tested and some winners will emerge. More startups will fail, few will win, founders & operators will recycle themselves into new ventures and the ecosystem will learn.

Let’s stop here and take a step back.

What is Venture Capital and why do we need it?

Does the VC model even make sense in Africa? The debate is open.

Some people famously claimed that Silicon Valley model doesn’t work on the continent, or that it needs serious re-evaluation.

Others say that it’s too early to judge.

To summarize, here are the reasons to be skeptical:

multiple markets & extremely fragmented (50+ states, different regulations, etc…);

consumers with low purchasing power & hard to acquire and retain, as they don’t tolerate fully digital modes of distribution;

capital markets aren’t deep enough to sustain startup growth (from Series A onwards);

low levels of physical, digital, and legal infrastructure (can you build ‘asset light’ on top of nothing?)

But there are reasons to be optimistic too:

we are barely 10 years in, so we haven’t seen an “exit” market at play out (and initiatives are emerging, like this);

tailwinds are here to stay, especially internet penetration & smartphone usage;

positive demographics & economic growth;

growing entrepreneurial talent

VCs invest in the equity of technology companies with very high growth potential. How high? High enough to reach significant revenue levels that justify high valuations, in a relatively short amount of time.

“Short amount of time” refers to 7–10 years, the period in which an early-stage fund’s stake in a startup should be converted into liquidity, primarily through M&A.

Startups = growth because 1) they are bound to conquer large markets 2) by virtue of some technology elements that 3) make them highly scalable/defensible businesses.

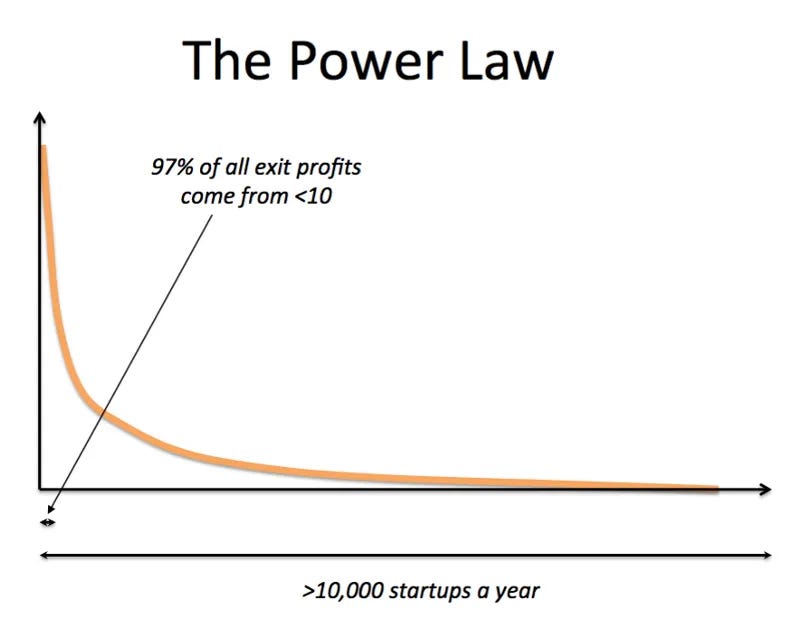

Successful startups are rare. The difficult nature of the task does not allow for many winners. In a startup portfolio, many will fail, others will struggle to grow beyond a certain threshold, and perhaps a few will deliver the famous “outsized returns.”

Which leads to the empirical phenomenon of the Power Law.

More than half of the companies do not return the money invested. The majority of exit profits come from a few companies. This is what VC always looks for: the 20x return. This is what every company in the portfolio should be able to do, but only a few will. In Africa as everywhere else.

So, where are the venture-sized return opportunities on the continent?

Fintech eats the continent 🏦

There have been less than 10 “venture-scale” exits in the continent so far, and they can be divided into two groups.

The first group is what I call “the japa boys”.

“Japa” is a popular Yoruba term to describe young people leaving the country in search of better opportunities abroad.

It’s well-suited to describe a set of companies headquartered in Africa that developed tech products for global markets from day one. Some of them also moved their HQ at some point in their growth history.

Examples are:

Instadeep, Tunisian AI startup founded in 2014 and acquired by BionTech in 2023 for $700M.

Expensya, another Tunisian spend management automation tool founded in 2014 and acquired by Medius in 2023 for ~$120 million.

PaySpace, a South African cloud-based payroll and HR platform founded in 2000 and acquired by Deel in 2024 for ~$100M.

The “japa boys” highlight the potential of Africa-founded products to serve global markets and subsequently get bought by larger companies.

The second group is what I call the “homegrown heroes”.

These are companies that became very big by solving African problems. Their main target customer is African businesses, consumers & diaspora. Also, they had to lay down foundational infrastructure to operate and, as it turns out, they are mostly fintech companies.

Members of this group are:

Sendwave, a remittance company founded in Senegal in 2014 and acquired by WorldRemit in 2020 for $500M.

Paystack, a payments API company founded in Nigeria in 2015 and acquired by Stripe in 2020 for $200M.

DPO Group, a Kenyan-born payment service provider founded in 2006 and acquired by Network International in 2020 for $288M.

Jumia, the “Amazon of Africa”, founded in Nigeria in 2012 and went public on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in April 2019, valued at approximately $1.1 billion.

To assess the “size” of these opportunities, let’s take Paystack as an example.

They raised their seed of $1.3M in 2016. At what price? It’s hard to find out online. Let’s assume a $10-15M post-money valuation. Simplifying, 1.3M gave investors 10% of the company. They went on to raise 8M Series A. Let’s assume seed investors got a 15%- 25% of dilution. This leaves them with 7% of the company. After the Series A, it sold for $200M to Stripe. This left seed investors with $14M.

It is a ~11x and can be considered a home run.

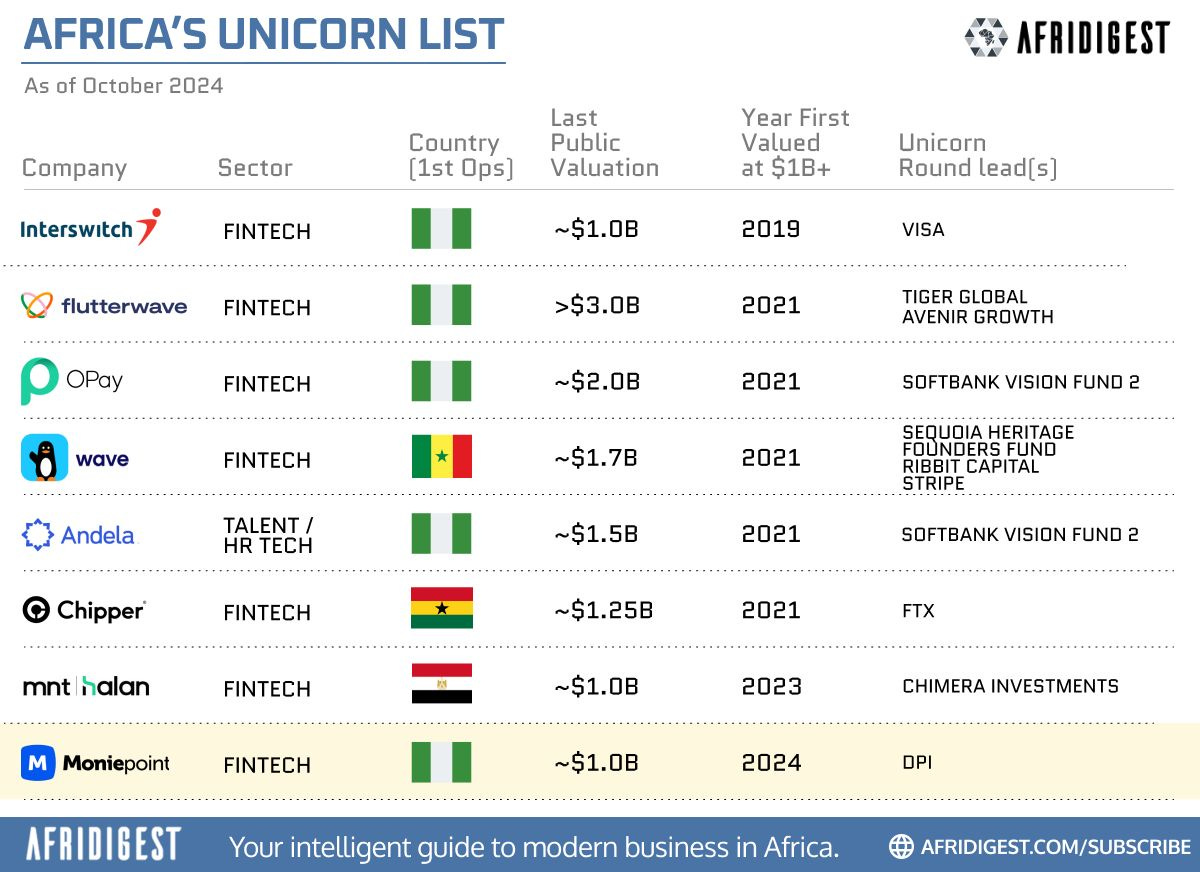

In 10 years of activity on the continent, VCs have learned one thing: if you’re looking for venture-scale returns, look at Fintech.

It’s not just the exits: 7 out of 8 unicorns in Africa are fintech companies.

The success of the category is justified by some facts:

everyone needs it, everyone uses it a lot (it’s not una tantum consumption);

high levels of financial exclusion making up for a large untapped market;

mobile phones completely flipped the distribution game;

it’s the basic building block of the digital economy.

This last point is critical. We can say that for every dollar invested in a digital business today, a % of that will become revenue for a fintech player.

In the words of David Adeleke in Communiqué:

“In Nigeria, for instance, fintech was the railroad on which the tech ecosystem was built. Legacy payment companies like Interswitch and newer players like Paystack and Flutterwave built critical payment infrastructure for thousands of businesses to collect money from their customers. They created a platform for many other startups to expand their product offerings and seek out venture capital. With reliable payment solutions in place, these businesses could focus on growth rather than pesky transaction-related challenges. Other tech sectors like logistics, edtech, healthtech, and e-commerce have also flourished because fintech had already done the thankless job. For instance, PiggyVest, a wealth management platform, was enabled by Paystack’s payment solution; Uber found it easier to deploy its ride hailing services in Nigeria because of Flutterwave’s payments rails; and Netflix and Amazon Prime could spread their tentacles and bill users in Nigeria because of payment infrastructure from local startups.”

We are 10-15 years in the making, and fintech seems to be delivering on its promises.

The question everyone is asking at this point is: what other sector justifies venture-scale returns in Africa?

Commerce: the (eternal) next big thing? 🛒

For a while, Commerce was seen as the most promising candidate for generating venture-scale returns.

And with good reason.

First, the retail sector represents a massive portion of consumer spending in Africa. Only Food & Beverages accounts for $1.4 trillion of spending in 2023. Capturing even just 5% of that spend could generate VC-kind of returns.

Second, the model has worked remarkably well in Asia. Outside of China, true e-commerce giants have emerged by leveraging a mix of digital experience and fulfillment. So why not in Africa?

Unfortunately, a pure e-commerce play revealed harder than expected. The first and only IPO of African Tech came from Jumia, often called the “Amazon of Africa”. As historic and important as that moment was, enthusiasm quickly cooled when the stock price plummeted by 75% and the company had to scale back its operations drastically.

As the mantra goes: Informal markets are hard to replace.

And we still lack a critical mass of smartphone users, last-mile logistics, and spending power to justify the model.

But we have millions of mom-and-pop shops serving millions of customers every day.

What if we used tech to empower small retailers, helping them manage inventory, digitize their operations, access financing, and work more efficiently?

This led to an obsession with B2B commerce and a funding “sprint” around B2B marketplaces.

B2B e-commerce startups have attracted up to $470 million in VC money, with 90% of the capital deployed between 2021 and 2022.

We know the names:

These are among the most valued companies in the continent, but hey, have you read the news last year?

Copia Global & Zumi shut down. MarketForce winded down its B2B marketplace arm.

Alerzo, Twiga Foods had to lay off employees and scale back operations.

Wasoko and MaxAB had to merge to survive.

It turns out that attracting growth capital in the ZIRP-era with weak unit economics led to a drastic re-sizing during the funding winter that followed. It is also worth considering that:

A lot of competition and “race to the bottom”: many startups engaged in discount wars to gain market share, leading to unsustainable pricing strategies.

Asset-heavy operations: Due to a lack of existing infrastructure, many startups had to build their own warehouses and delivery systems, making their business models capital-intensive and more costly to scale;

Valuation traps: High valuations driven by VC funding created pressure to meet ambitious growth targets, trapping startups in a cycle of excessive spending and compromising their valuation (to get the mechanics of it, I suggest you read this brilliant article by Ryan Shannon)

Sure it was a matter of wrong timing, but this also highlights the complexity of addressing Africa’s fragmented and informal markets, even with innovative B2B solutions. It is hard to make good money.

I am not claiming startups addressing the commerce/retail sector are doomed to fail. In fact, I think many will survive and become very successful.

A good example is Omniretail. It is the fastest-growing company in Africa in 2024. Its value proposition? Digitize the FMCG supply chain, from manufacturers to retailers. Starting in 2019, they have “only” raised $20M in debt and equity, and achieved EBIT profitability with $140M in revenues in 2022.

The sector will have its winners: it will take longer, and just fewer than less foundational than fintech.

And all the rest? 🏥📚

Beyond, Commerce, we’ve heard of other candidates too:

Jobtech

Agritech

Edtech

The “hype” around these sectors has been justified by the existence of real, large opportunities:

Africa will soon be the largest net contributor to the working-age population globally;

Africa has 60% of the world’s uncultivated arable land and the lowest grain yield in the world;

Africa has the largest population of young people in the world and among the lowest school participation rates.

If we do some napkin math, we can easily imagine how a company could capture a fraction of these markets and justify venture-scale returns.

The problem is: at what cost?

It is not enough to go after these giant opportunities. In VC-landia you need:

Some asset-light / scalable business model → it’s harder to grow fast if you need to debt-finance capital expenditure;

To scale cross-border → the opportunities are big only when you look at the whole continent (54 states), so cracking one country is not enough;

To build a defensible business → a lot of problems could be solved by having a competitive market with 20+ companies each having 5% market share. While good for consumers and the economy, it’s not attractive for VC. What is the case for consolidation / winner-takes-all scenarios?;

To (eventually) make good money → retain your customers and earn more than you spend.

We did have some companies ticking these boxes that have grown impressively so far:

Winners are sparse, and not really as concentrated as with fintech.

How can we interpret it?

There are two opposing schools of thought.

The first emphasizes the unique capabilities of exceptional founders, who are seen as the driving force in identifying hidden opportunities and transforming them into successful ventures. In this view, the primary role of investors is simply to provide funding to support the founders’ vision.

An extreme example of this philosophy is Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, which operates on the belief that true entrepreneurs don’t require guidance.

It goes like this:

“It doesn’t matter what sector you look at, outstanding entrepreneurs will emerge and build extremely successful companies”.

For them, the emergence of great companies is somewhat uncorrelated to the sector. If fintech is hot, it’s because the best founders are attracted to it. But it tells us nothing about what sector we should bet on next.

The second approach believes macro-opportunities can be proactively identified and companies can be explicitly built around those. It is the Venture Studio model, what Rocket Internet did with Jumia, and what MStudio is doing for Francophone Africa.

It goes like this:

“There are transformative forces consistently shaping all emerging markets. By analyzing and anticipating these trends, you can build very successful companies”.

For them, fintech success is the natural product of such transformative forces, and it is somewhat possible to predict the next big wave.

I believe the truth is likely a mix of the two, with one additional element: early-stage investors are very sensitive to narratives. Who is shaping current narratives, how, and why? To me, it has a direct impact.

Wrapping up 🌯

Successful startups are rare. Whether it’s by copy-pasting or the magic gist of entrepreneurs, there will be very few home runs for each generation.

Fintech has delivered on its promise and will continue to in the coming years.

Commerce too, but with many $$$ burned along the way.

All the rest is highly uncertain and volatile.

But ultimately, does the VC model work for Africa? I believe it does. It just needs some fine-tuning along the way.

But maybe most importantly, we should remind ourselves that startups are not the solution to Africa’s development challenges.

Most businesses are not startups and don’t need to be.

There are so many ways of financing innovation, employment, growth, and impact.

One good example is Untapped Global, and I wrote about it here.

Another one is AgDevCo, which is doing a great job investing in agribusinesses with a mix of equity, mezzanine debts, senior debts, and working capital.

Let’s stop portraying VC as the salvation of the continent, capable of leapfrogging the continent into a techno-utopia. Instead, let’s see it for what it truly is: the high-risk pursuit of rare outliers to achieve outsized returns.

By no means this should be the backbone of a country.

when do you think the pendulum will swing back to normal business? We can't eat software and yet lots of normal agri business and homes are still needed. Strange that those sectors haven't seen many startups... or maybe they are just hidden.