Powering the next billion - Part I

Electricity access, reliability, and cost: checking Africa’s progress so far

Question: why do we care about electricity?

Answer: because we care about economic & social development.

The two go hand in hand: high-income low-energy countries don’t exist.

And if GDP statistics are too cold for you, plenty of academic research shows the positive impact of electrification on:

Electricity is an enabler: it allows us to do more with less. To unlock its full benefits, we want it to be:

accessible → can I plug my device and use it?

reliable → can I trust that it will work most of the time?

cheap → can I afford it?

Let’s jump on a healthy excercise: scan the African context vis-à-vis these 3 key measures.

Access: just half way through 🚶🏽➡️

One day, three years ago, my father called me, his voice filled with joy. “They’ve installed electricity poles in Kperedy!” (his home village)

I was puzzled. “What do you mean? And before?”

“Ah, before there was no electricity.”

Speechless, I tried hard to imagine a life without electricity.

In Africa, 600 million people, or 43% of its population, lack access to electricity.

And yet, globally, electricity access is a success story. In the world, 91% of the people have access to electricity. Of the remaining 9% - 720 million people - the majority are in the continent.

The situation is pretty bad for countries of the “Central Belt” (Burkina Faso, Niger, Centrafrica, Chad, South Sudan, DRC), while North Africa is almost fully electrified. The rest is mixed, with Ghana leading West Africa and Kenya East Africa.

Progress has been made in the past 30 years: electricity access in Sub-Saharan Africa grew from 28% to 51%.

Some countries did better than others.

In 1996, Kenya and Tanzania had similar levels of electricity access. Fast forward 30 years, and Kenya has a 76% electrification rate vs 45% in Tanzania.

Part of it can be explained by a push from governments with so-called “rural electrification programs”.

In 2006, Kenya established the Rural Electrification and Renewable Energy Corporation (REREC), to accelerate the pace of rural electrification. REREC alone helped grow rural electrification from 4% to 32% of rural households.

More recently, Tanzania has tried to mimic Kenya’s success with similar programs. In 2017, the country launched the Tanzania Rural Electrification Expansion Program (TREEP), which helped it achieve one of the fastest expansion rates in Sub-Saharan Africa: 4.5 million new connections in just 5 years!

These programs have played a crucial role in driving adoption where market incentives are weak, leading to significant progress in expanding electricity access. However, we shouldn’t declare victory too soon.

First, recent research suggests that rural residential electrification does not appear to have meaningful impacts on household incomes among the extremely poor. Why? Well, once people have access to electricity, they also need to use it. If you don’t have money to buy productive appliances, then you won’t use much electricity. Powering a simple TV set doesn't yield the same benefits as powering a washing machine business.

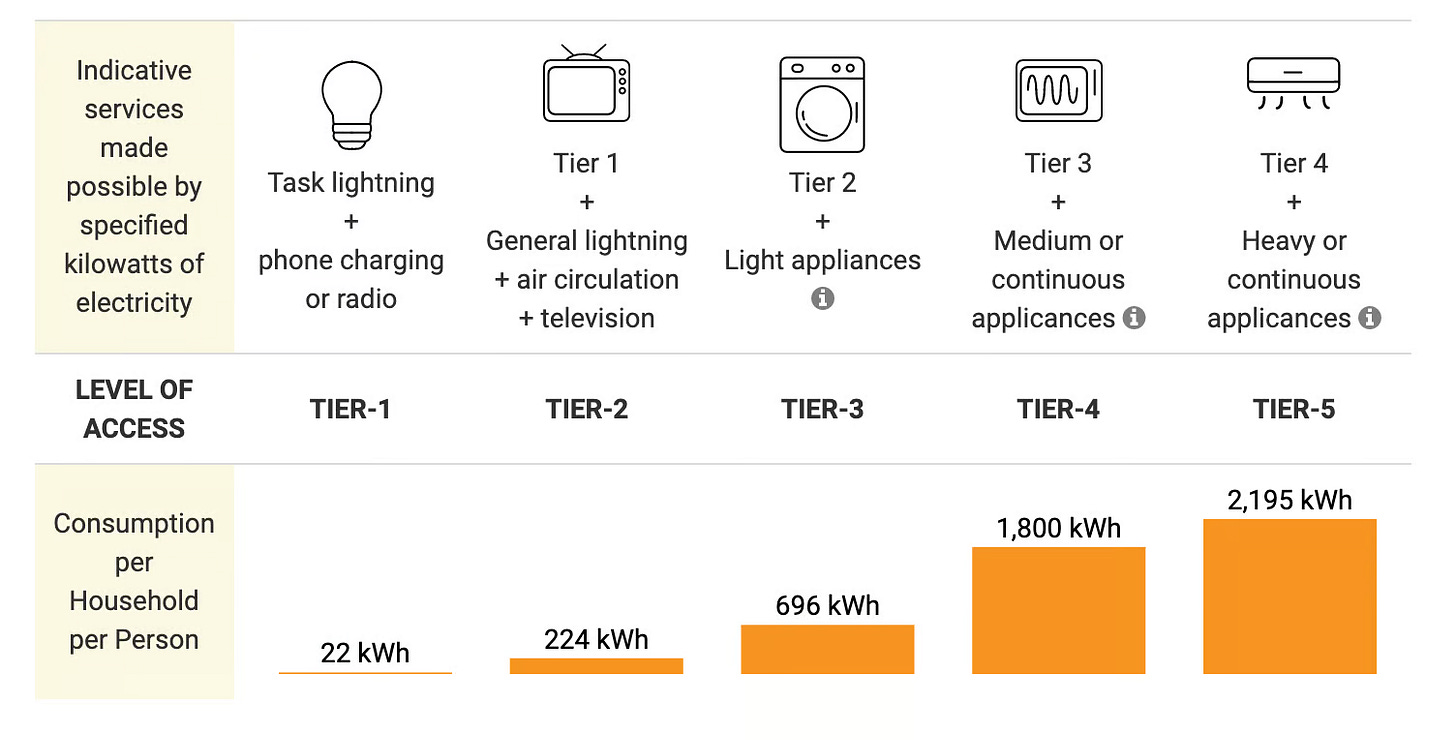

Electricity access is not a boolean TRUE / FALSE variable, but a spectrum ranging from zero consumption to low consumption to high. The World Bank (recently) divided energy access into Tiers, based on the amount of kilowatt-hours consumed. How many of the 9 million electricity users in Kenya are Tier 1 vs Tier 4-5? We don’t have statistics yet, and it’s a critical gap, given the significant socio-economic implications.

Secondly, even in countries with low electricity access rates, there is still a massive urban-rural divide. Example? 40% of Nigerians don’t have access to electricity. If we unpack it along the urban/rural divide, we have:

11% of the urban population without access

73% of the rural population without access

For city dwellers, electricity access is almost at 90%. Isn’t it enough then to locate all your productive businesses close to the cities and solve most of our problems? Well, no! Access is just one piece of the puzzle. We also need electricity to be reliable. And increasing body of research shows just how much the latter can be a much more critical factor, especially for productive uses fo electricity.

Reliability: the “hidden” cost of access 🫣

People might be listed as ‘connected’ when they first get connected to the grid, but fewer than 20 percent of Lagos residents report that their power, once connected, works ‘most of the time’

This is an extract from an excellent article by Lauren Gilbert: ‘Every generator is a policy failure’. The article raises critical points:

African governments’ obsession with expanding electricity access has pressured utilities to keep tariffs artificially low, often below the actual cost of supply;

As a result, many utilities are financially strained and unable to invest in infrastructure and maintenance;

which leads to poor grid reliability, i.e. frequent power outages

I believe electricity reliability is at least as important - if not more - than access.

Frequent power outages negatively impact the productivity and profitability of SMEs, and African firms lose between 2% and 15% of the value of total annual sales due to electrical outages. It makes sense: when I moved to Accra, blackouts were so frequent to the point that I couldn’t store anything in the freezer. When power is unreliable, its benefits disappear with it.

On the contrary, research in developing countries demonstrates how reliable electricity provision increases energy consumption as households invest in new appliances, thus generating more revenues for utility companies, and moving the people upward in consumption Tiers.

When the grid is unreliable, households and businesses rely on diesel generators as their main backup plan for when electricity is off.

Have you ever wondered why many African cities are filled with a unique thick & stinging gasoline smell? According to some estimates, Nigeria can get about 40,000 megawatts of electricity from gasoline-powered generators. If run at full capacity, it’s enough to power around 100 million homes in a typical middle-income country! 🤯🤯🤯

Diesel generators are the de facto economic (and environmental) tax of poor electricity reliability.

But how do we measure reliability? And how can we know if we are making any progress?

One of the most reliable ways to assess this is by calculating the total duration of grid interruptions over a year. This is measured using a global standard called SAIDI (System Average Interruption Duration Index), which measures the total duration of power outages per customer per year (in hours). Ideally, utilities are responsible to publish this metric regularly, although in many African countries, reporting is inconsistent.

The World Bank has done an amazing job at aggregating (most) information for (most) utilities in the continent, with the creation of a platform: UPBEAT. On it, all the most important indicators measuring financial and operational performance, with international benchmarks.

If we look at SAIDI, reports of utilities in Africa show high variability across countries. In 2020, for example, we go from:

Zambia GESCO, reporting 1.19 hours of outage per year, to

Guinea’s EDG, reporting 175 hours of outage per year

Overall, looking at the available data from utilities across the continent, there seems to be a downward trend in power outages.

But it’s not all smooth sailing.

For example, Ghana’s ECG saw a decline from 167 hours of interruptions in 2013 to 55 hours in 2019—a clear improvement, right? However, beyond that, data is scarce, making it difficult to track progress further.

If we look at ECG’s official documents, in the second quarter of 2023, they reported 24 hours of power interruptions. If we extrapolate that over the entire year, it amounts to 96 hours—indicating a significant deterioration, likely driven by the country’s worsening fiscal crisis.

Looking at another example, Côte d’Ivoire provides a more consistent reporting framework, allowing us to observe a mild downward trend: from 46 hours of interruptions in 2012 to 29 hours in 2022.

Overall, we must still be cautious because:

SAIDI often only accounts for distribution-level outages, meaning larger systemic issues may go unreported (like generation & transmission failures);

Also, many utilities exclude planned load shedding (rolling blackouts) from SAIDI calculations, even though it directly impacts consumers.

In short, SAIDI doesn’t account for all connectivity issues, but it serves as a good indicator of quality of service (i.e. reliability), especially when utilities consistently report data.

Now, one last element remains to be analyzed: cost.

Cost: the “visible” hand of governments ✋🏽

Electricity is not for free: it comes at a cost. And not just for the final consumer, who pays the electricity bill; also for the utility who produces it: the cost of generating it, the cost of distributing it, the cost of maintenance of equipment etc…

Ideally, we want to have:

Consumer cost = utility’s costs (CAPEX, operational…) + utility’s margin

Is it always the case? No.

In Africa, the end-customer cost of electricity varies a lot from country to country - and it is measured in USD x kilowatt-hour. We go from countries like Kenya, Rwanda, Gabon, where residents spend o average 20 cents per kilowatt-hour; to coutries like Angola, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Egypt, where they spend 2 cents per kilowatt-hour. A 10x difference!

Where electricity is very cheap, usually the country benefit from vast natural resources that are either used to produce electricity directly (like massive hydro power investments in Ethiopia and Egypt), or contribute to government revenues, who in exchange, heavily subsidizes electricity consumption (Nigeria, Angola, Sudan etc…).

This is a problem: most utilities do not have cost-reflective tariffs. It means that the tariffs charged to the end customers are not reflective of the real cost of generating electricity and distributing it. They are almost always lower. The reason is political: governments keep prices artificially low (with subsidies) to favor access and earn votes.

From the figure above we can see that, with the exception of Uganda and Seychelles, in all African countries unit costs of producing electricity are more than what is billed to customers, per kilowatt-hour:

“utilities without costreflective tariffs and sufficient revenues skimp first on capital expenditures and then on maintenance, and finally they cannot even cover operating expenses, resulting in deterioration and perhaps even a collapse of electricity services” (source)

And here we close the loop: cost impacts reliability.

On the one hand, with a median tariff of 0.15 USD per kWh, Africa has among the highest electricity cost in the world. That’s not terrible per se, but when you combine it with the highest poverty rates in the world, it becomes way harder to boost residential consumption, who in turn reduces utilities’ revenues.

On the other hand, even with current electricity tariffs and consumption levels, costs of electrcity generation & distribution are not re-covered. Utilities become loss-making businesses, and can be sustained as long as the government can finance its debt and “socialize” these losses through subsidies. But when an external shock occurs—such as in Nigeria, where a combination of naira devaluation and a fiscal crisis disrupts the supply of gas to power plants—the situation quickly deteriorates. Gas to power your plants becomes more expensive, government has less money, and the energy crisis worsen.

Yoyoyo!

In the upcoming episodes of this series, we will explore more in detail the electricity value chain, from generation to distribution. We will take a closer look at the most important innovations in the sector and hint at what policies we can incentivize to make the continent stronger and energy independent, laying a solid foundation for industrialization and sustainable growth 🫡👋🏻

Great post! What do you think of the push for electric vehicles (from motorcycles to cars to big trucks/buses)?